I left Egypt in late May, less than 48 hours ahead of a Cairo Court arrest warrant for foreigners "promoting democracy."

A month later, June 30 could end up having been the watershed moment for the new Egypt. Perhaps by the time you read this, it already has. June 30 is the first anniversary of the government of the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist movement that many secular Egyptians fear wants to turn the country into a theocracy. Following the overthrow of the dictator Hosni Mubarak in 2011, the Brotherhood, a semi-secret society, won the country’s first real elections. It won, not because most Egyptians liked or trusted it, but because, operating in exile or at least in shadow for 85 years, it was far better organized for winning elections than the dozens of secular and liberal parties that sprang up only in the wake of the January 2011 Revolution.

Perhaps influenced by its decades as a pariah, however, the Brotherhood government of Mohamed Morsi has from the start played defense, focusing on its own survival more than trying to solve the country’s enormous problems, mostly economic, that worsen by the day. Its ineffectiveness has undermined whatever mandate it may have gained in the 2012 elections, so that its worst fears are now a reality. The Morsi government is now fighting for its life, battling secularists on the left, a well-organized party of Islamic fundamentalists (called Salafists) on the right and a semi-independent court system somewhere in the middle.

Meanwhile, the secularists and liberals have squandered the momentum of their magnificent 2011 Revolution by fighting with each other. Dozens of new parties on the center and left have sprung up over the last two years, each seemingly incapable of the kind of compromises needed to forge a unified front that could be a competent electoral challenge to the Muslim Brotherhood. Across the political spectrum, there seems to be little or no sense of a broader positive vision for the country, to say nothing of the will needed to make such a vision real.

The result is political gridlock and an economy in a tailspin as both foreign investors and tourists stay away. Prices of staples have skyrocketed. Government services are a mess. Piles of garbage lie uncollected on the streets. Even the traffic cops aren’t showing up for work, so Cairo’s already bad traffic becomes impossible.

Energy is a huge problem. Egypt has antiquities, not oil. With foreign investment and tourism scared off by the political unrest, there’s not enough foreign exchange to buy enough fuel to meet public needs. So power plants and generators go offline for lack of fuel. Vehicles line up for hours to buy scarce supplies of gas. Trucks don’t deliver goods.

It’s not just the country’s governance and economy that have been spiraling downward. “Life here got lot uglier after the Revolution,” an Egyptian friend told me on a street corner in Alexandria. She meant that the new freedoms had unleashed a flood of individual expression and not all of that was positive. “Freed from the rules (of a top-down state),” she went on, “we Egyptians became much more critical, much less tolerant of each other.”

I could see for myself what she meant. In the subway, for example, those waiting to get in the cars don't wait for those wanting to get off; they charge ahead, delaying trains and fraying tempers. Cairo relies more on traffic circles than traffic lights but there are not nearly enough traffic cops coming to work these days and no accepted rules of the road, so every major intersection is a hair-raising game of chicken. I was delayed in a two-hour traffic jam on the road from Alexandria to Cairo because drivers behind the jam, refusing to wait, swerved left to drive in the oncoming lane which, of course, increased delays in both directions.

Yet, despite all of this, I left Egypt a month ago hopeful for the country’s future. The 2012 Revolution in Egypt may have released the worst in its people, but it also released the best. Still held together by 5,000 years of a common, illustrious history, the people of Egypt have the brains, culture and spirit to move the country forward.

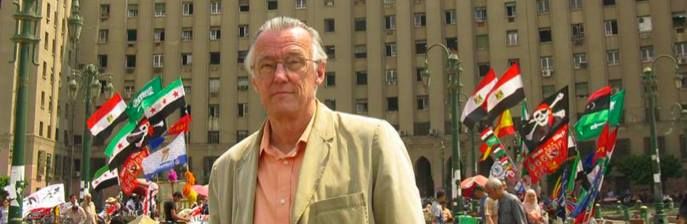

I spent ten days in the country representing Giraffe Heroes International (GHI), an American NGO whose global mission is to move people to stick their necks out for the common good, and to give them tools to succeed. I was in Egypt to help launch ”Giraffe Heroes Egypt,” an independent Egyptian movement whose purpose is to blanket the country with stories of Egyptians who are acting (or have acted) with courage and compassion to solve significant public problems. Others will hear and see the stories of these “Giraffe Heroes” and be inspired to reach across divisions to build the stable, just and prosperous democracy most Egyptians say they want.

A simple-minded strategy? Perhaps. But telling the stories of heroes has motivated people to do public good for thousands of years and in every culture. And it works today. GHI’s parent, the Giraffe Heroes Project, has been doing it in the US since 1982. Over the last four years, we’ve launched Giraffe Hero movements in Nepal, Sierra Leone, India and the Muslim community in the UK.

I found plenty of support for such a movement in Egypt--at Cairo University, in the remarkably free media, and in talks with businessmen, NGO leaders, entrepreneurs and politicians. Admittedly most of my contacts were with people critical of the Morsi government, but there were enough exceptions to convince me that the whole country could pull together if only the inclusive vision and the leadership behind it were strong enough.

I was, for example, twice invited on a television station controlled by the government to explain the purpose of my visit. I described to a national audience how a focus on heroes could inspire all Egyptians to take the risks to bridge the differences that were tearing the country apart. I also said the obvious: unless Egyptians can figure out a way to come together to rule themselves, they invite terrible violence and the return of a dictatorship; the sacrifices of 2011 will have been in vain.

As part of my visit, I led three training workshops for change agents. To my surprise, my audiences wanted coaching, not so much on handling the “big” questions, such as energy and party politics, but on dozens of small-scale projects. This focus wasn’t because they were timid, but because they were smart. Mustapha, for example, a city planner, was working to create bike lanes to ease traffic congestion in Cairo. His point wasn’t just that bike lanes could ease traffic and cool tempers. Projects like bike lanes could show Egyptians that they could, even with no or minimal government help, relatively quickly make at least one part of their society work better. Rana, an architect was creating low-income housing by using clever designs to build tiny but livable dwelling spaces in low-income neighborhoods. All over Cairo, it seemed, young people had started “incubators”—small office spaces where entrepreneurs gathered in small groups to trade ideas and to launch projects not just to make money but to actually solve the country’s problems, starting at the grassroots.

With government gridlocked, other citizens have simply taken matters into their own hands, from directing traffic to guerilla rehabbing of old housing. One neighborhood group, tired of waiting for government bulldozers, even built its own on-ramp to a passing thoroughfare.

There are some encouraging large-scale changes too. New cities are springing up on the road north of Cairo, for example, and a massive business park called Smart Village has attracted a Who’s Who of global corporations.

Egypt is ready to move forward. But the country needs an inclusive, motivating vision and the courage and examples to make it real.

Telling the stories of the country’s heroes, past and present, will strengthen all these elements. And as to the practical examples needed to build people’s confidence and hope—start with the bike lanes. Egyptians need to trust each other enough to rise above religious identities to solve public problems together. This civic work must be done at a national level, but that is not happening now. So the examples must well up from underneath. From bike lanes. From showing people better ways of getting on a subway car. From neighborhood meetings that solve neighborhood problems. If the people of Egypt can finally organize themselves to go around a traffic circle without chaos, they can organize a government that works. Many people understand this.

It will take courage, patience, smarts—and a flood of examples of heroes acting bravely for a common good. Let the politicians learn from the people.

Egyptians need to get this right. And they don’t have a lot of time.