In late March, I helped Nana Darkwa set up Giraffe Heroes Ghana (GHG), the newest affiliate of Giraffe Heroes International. GHG will find courageous Ghanaians working for peace, then tell their stories to the nation, inspiring others to follow their leads. The purpose is to help ensure that November's highly contested elections here will be free, fair and non-violent. Part of the work was a major speech I gave at Accra's International Conference Center. It went over so well--I post it here.

Peacebuilding in a Violent World

John Graham

A New Narrative

Speech by John Graham, International Conference Center, Accra, Ghana March 24, 2016

I lived almost next door to you for two years.

My first post as an American diplomat was in Liberia, in 1966. Then I was sent to Libya, where I was in the middle of the first Libyan revolution in 1969. With anti-US mobs in the streets, I did the first biographical report on Muammar Qadhaafi because in 1969 neither the US government nor any other foreign government knew who the heck he was or where he’d come from.

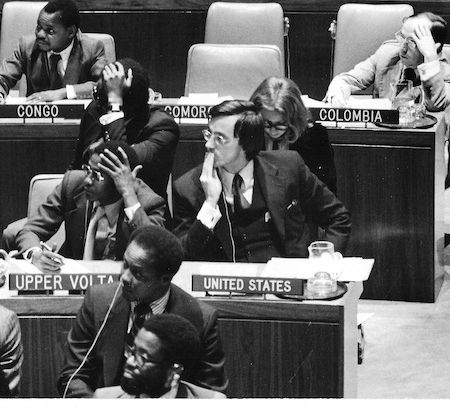

Some years later, my last post in the Foreign Service was as chief for African Affairs at the US mission to the United Nations, where my responsibilities covered the entire continent.

I know Africa pretty well, I have many friends here, and great affection and respect for its peoples.

I also know something of its politics.

I know, for example, that the reality or threat of violence is never that far away on this continent. I understand the fear caused by recent jihadist attacks on your neighbors. I also know that violence between and within African states is still driven by the legacy of colonial divisions, tribalism, political, religious and ideological splits and classic competitions for power and resources.

Now add, for Ghana, a hotly contested election in November.

Could there be election-year violence in a country as nominally stable as Ghana? To those who say, “No,” I remind you of what happened in Kenya just five years ago.

So I’d like to offer some thoughts, focused mostly on the internal threats to peace here in Ghana.

I’m not ignoring Al Queda and Boko Haram. The jihadists will be destroyed, not by military action alone, but by economic and psychological attacks that degrade their ability to attract recruit and fund their operations. Meanwhile, Ghana’s security forces are competent—there’s a reason the UN keeps asking them to participate in its peacekeeping operations.

Still, we must be blunt. There’s no way to protect every soft target from suicidal attackers, whether here or in California.

Let me say this: it would, in my opinion, be a huge mistake for Ghanaians to over-focus on the jihadist threat. That’s exactly what the jihadists want you to do. Jihadists win not by body count, but by terrorizing, demoralizing and distracting people so they lose hope and focus and so the governance fabric in their countries starts to shred; that’s when the real problems start.

Don’t let that happen here. Keep your heads on and keep your heads up.

With that in mind--

As we all know, political violence erupts whenever the forces pulling people apart are stronger than those that keep them together. Those disruptive forces can include corruption, historical grievances, ignorance, fear, economic inequalities and bad leadership…. They all lead to mistrust, the mistrust leads to stereotypes, the stereotypes ramp up fear until violence can become almost inevitable.

The groups in conflict can be tribes, political parties, haves versus have-nots, religions or regional identities. As anyone who’s been watching Donald Trump’s political rallies in America knows, I’m not just talking about Africa.

In Ghana as elsewhere, the resources to suppress violence include armies and police forces, but more importantly a stable web of institutions in government, business, media and civil society that can provide social and political glue.

But you know all this--so I want to go a little deeper today, as a tough old diplomat who’s seen and been a part of a lot of violence, someone with a lot of scar tissue on his back, someone who’s nobody’s fool.

Given this, my experience and conviction is that the ultimate counters to violence are not found just in security forces and stable institutions, although both are certainly important. Peace must start in individual human hearts.

That means creating a new narrative, a new way of living, for our lives and for our country’s life (in Ghana or in America), strong enough to replace the old narrative fueled by those disruptive forces of corruption, grievances, ignorance, fear, economic inequalities and bad leadership.

The best people I know to teach us about this new narrative, this mainstay of peace, are Giraffes.

I don’t mean four-legged giraffes. I mean the two-legged heroes honored by the NGO I help lead, the Giraffe Heroes Project. We call them Giraffe Heroes because they stick their necks out to make the world a better place and we use the metaphor “giraffe” for them because giraffes have the longest necks.

Giraffe Heroes are men and women, young and old, from every ethnic and economic background, from over 60 countries. They’re tackling every kind of public problem, from racism to climate change, to gang and tribal violence, to crimes against women. If there’s a public problem, there are Giraffe Heroes working to solve it. Over 34 years now we’ve honored over 1300. Giraffe Heroes are people like:

Henri Ladyi

In the war-ravaged Democratic Republic of Congo former schoolteacher Henri Ladyi works constantly for peace, disarming militia fighters and helping them rejoin their communities, helping displaced people get back to their homes, resolving conflicts, and rescuing thousands of children—some as young as seven—who have been abducted into violent militias. Ladyi persists despite the constant danger that he’ll be killed for his efforts.

“I am looking for peace,” Ladyi says. “I am searching for solutions. I go to them, the militiamen, and ask them, ‘Please, my friend, it is time to leave the bush. It’s time to stop living the life of the gun. It is time to end the militia. Put down your gun and come with me.’ And sometimes they follow me out of the forest.”

Joel Bisina was a successful banker in Lagos when he realized that the impoverished rural region where he was raised needed him to come home. Oil extraction by multi-national corporations was damaging the environment of the Niger Delta. Oil was leaving the Delta--along with the profits from its sale. Nigerians in the area were poorer than ever and many of them were angry enough to become violent. Bisina now runs Niger Delta Professionals for Development, organizing Deltans to work for economic justice—peacefully.

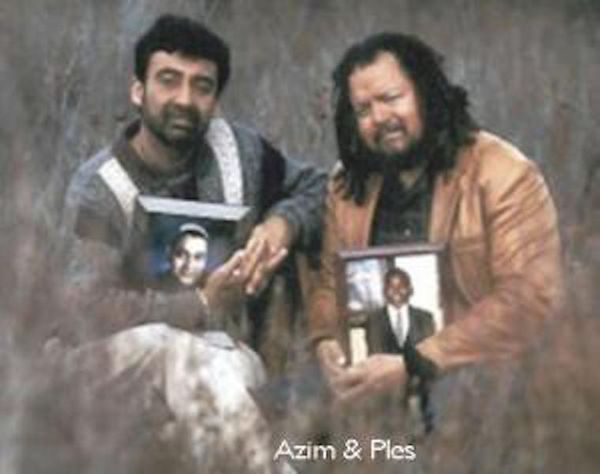

The bond of friendship between Azim Khamisa and Ples Felix, two Americans, is strong, resolute, and born out of shared tragedy—Felix's grandson shot and killed Khamisa's son as part of a gang initiation. Now the father and the grandfather work together to end youth violence and to reform the criminal justice system in the US. When children kill, "there are victims at both ends of a gun," says Khamisa.

Hanna Hopko braved snipers’ bullets in Kiev, Ukraine during a people’s revolution that brought down the corrupt Ukrainian government. She now leads a rapidly growing group of citizens who are creating a legislative revolution in Ukraine, drafting new laws and policies for fair and open government, then lobbying to have them adopted by their new Parliament. Her car was destroyed and her life has been threatened, but ten of her group's proposed laws have already been adopted and Hopko and her group are pushing for more.

In Burundi, a country devastated by ethnic conflict, Prosper Ndabashuriye brought Hutus and Tutsis together to build new houses for those who had lost everything. Despite threats, financial nightmares and even imprisonment, Ndabashuriye and his multi-ethnic team built hundreds of houses for their fellow Burundians.

Aida Marini of Beirut, Lebanon, the most celebrated female artist in the Middle East, refused all offers of safe haven abroad during her country's years of war. Marini remained in Beirut, working in an apartment with blasted windows and no water, using the art she made there to promote the cause of peace in Lebanon and around the world.

Despite being shot at by members of political parties and threatened by government officials, Nana Yaw Osei-Darkwa works to make Ghana a peaceful place. Through his organization, Youth Icons, Osei-Darkwa teaches and motivates Ghana's youth to help create that peaceful future. He’s trained hundreds of Ghanaian youth and has spoken at conferences and other events around the world to convey messages of peace and responsibility. We are here today to help support his work.

And there are 1300 more stories like these. Read them at www.giraffe.org

Our strategy at the Giraffe Heroes Project is simple:

We find these Giraffe Heroes and we tell their stories in our publications, on our website, in schools and in traditional and social media. Others see or hear these compelling stories and are inspired to solve the problems of most concern to them. We supply materials and trainings to help them succeed.

Yes, it’s that simple. And as it has for thousands of years, storytelling works. It really does change people’s attitudes and move them into action in ways more powerful than admonitions and threats. And we have the mountains of anecdotes to prove it.

As you might expect, we try to learn what makes these extraordinary people tick. Why do these Giraffe Heroes do what they do, why they take these risks and work so hard? Nobody pays them to do it. Nobody orders them to do it.

Many of them tell us, in so many words, that ours is a foolish question. The problem or conflict was right in front of them, they’ll say, and nobody else was acting—so what else were they supposed to do?

But the more you talk to them the clearer it gets that Giraffe Heroes are motivated by a strong sense that what they’re doing is meaningful to them—that is, that it satisfies a personal sense of purpose at the core of their being.

It’s this deep conviction that then drives them forward. It’s what makes them so effective in solving problems and so inspiring to people who hear their stories.

None of this should be strange to us.

Philosophers and holy men have told us for millennia that there’s no more powerful yearning than that our lives be meaningful, that we have a purpose that makes sense to us deep inside, that drives us and guides us in a totally satisfying way.

Don't take their word for it or my word. Look to your own experience. We all want to be able to look at ourselves in the mirror and know that our lives are meaningful, that what we’re doing counts, that we're not just on this planet to take up space.

Look to your own experiences—at home, at work, in the community. Like Giraffe Heroes, you may work very hard and there may be trials, but when you’re doing something you know is meaningful to you, there's also energy, a sense of excitement, a deep satisfaction of being in the right place at the right time. You’re more inspiring to others, and they're attracted to join you, to follow your lead. You do your best work and get your best results.

Have you experienced this? Do you know what I mean?

OK, if meaning is this important, it’s fair to ask—

Where does one find such meaning for a life?

In yearning for some apocalyptic battle against those who don’t share your religious beliefs?

Perhaps for a time.

Can you find it by collecting a lot of money and power?

Yes, many seem to find meaning in that, at least for a time

But I don’t think, and I don’t think you do either, that such sources are very stable or very satisfying over the long term.

And again, we go back to Giraffe Heroes for guidance.

Almost universally they tell us, with their actions and their words, that the most powerful, stable and satisfying source of meaning in their lives is service—

Helping solve important public problems,

Being changemakers and peace builders.

Making life better for other people.

Being of service drives them to do what they do.

Time after time we see and hear this, across all ages and ethnic groups, across continents and cultures—it’s the personal meaning they find in service that motivates and sustains Giraffe Heroes to take on difficult tasks and succeed. That’s the core of their stories, and it’s the basis of the powerful new narrative we’re seeking, a new narrative of peace, courage, responsibility and compassion.

It’s the perfect counter to the old narrative that threatens us today, the narrative based on corruption, grievances, ignorance, fear, economic injustice and bad leadership.

Do you hear this new narrative in your own heart?

Well, I didn’t, not for a long time.

As a young man, I was pretty sure what made my life meaningful. It was adventure, not service, and the bigger and the riskier the better.

I went to sea in a cargo ship when I was seventeen. This was, mind you, way before container ships. Cargo vessels had crews of 50 or 60 really tough seamen, all of whom were determined to teach me lessons they knew I would never get in school.

And sure enough, roaming around the Far East as a 17-year-old opened me to a huge vision of a wider world, pulsing with energy, colors and excitement. I wanted more.

I spent the summer after my sophomore year in college hitchhiking in Europe and North Africa. I walked into Algeria just one week after ceasefire had supposedly ended a brutal colonial war there. The situation was very fragile. At least I had the sense to pin a US flag on my shirt. Its intended message was: “Don’t shoot me, I’m not French.” Rebel patrols stopped cars going in my direction and told the drivers to take me where I wanted to go.

The next summer, 1963, I was part of a team that made the first direct ascent of the North Wall of Mt. McKinley, the highest mountain in North America—a climb so dangerous nobody’s done it since.

I kept upping the ante.

After college, I hitchhiked around the world.

I had a Press Pass from the Boston Globe newspaper and I used it to see and write about wars in Cyprus, Eritrea, Laos and Vietnam.

So by age 22, I’d gained the following perspective on life: This was my narrative at that time:

1) There is a huge wonderful, exciting world out there.

2) Nothing mattered but physical adventure, the bigger and riskier the better.

3) I was indestructible. None of my adventures would ever do me in.

To say that this narrative was shallow would be generous.

But I gained a lesson from those early experiences I’ve lived by ever since.

That lesson is that a full life invites passionate involvement, and that means sometimes taking risks.

But this lesson needed to be tempered with another lesson, one I didn’t get until much later.

This second lesson was this:

What’s important is not the risks.

What’s important is knowing what to take risks for.

The most significant risks often challenge not the body but the soul.

They’re about finding what makes our lives truly meaningful and then going for it with everything we have.

As I said, this second lesson was lost on me as a young man. The risks I took then were all physical. I did what I did because of the adrenaline buzz.

After that year spend hitchhiking around the world. I was faced with a challenge. How could I earn a living and still lead an adventurous life?

The answer was the US Foreign Service, which I joined in 1965.

It didn’t disappoint. I was in the middle of the Revolution in Libya in 1969, as I said, then I went to America’s war in Vietnam.

I went as a volunteer.

But I was no patriot.

I did what I did in Vietnam because I loved the adventures of being in the middle of a brutal war. I was appointed US Advisor to the City of Hué in the northern part of what was then South Vietnam. There I soon discovered how much I also loved the power that role gave me to make huge decisions and bear huge responsibilities as a relatively young man.

But my attitudes toward war and violence changed in Vietnam and that change began during a battle. Hué had been under siege by the North Vietnamese army and advanced units of the enemy were only 10 km away. The city was in great danger of falling. Many South Vietnamese officers had fled south to save themselves. Deserters from the South Vietnamese army had set fire to the marketplace and a heavy pall of black smoke hung over the city. Artillery boomed. Panicked people screamed. It was a scene from hell.

My job then was to try to deal with the looting and chaos in the city. Not knowing what else to do, I urged the mayor to set up a firing squad to start shooting the army deserters in order to dampen the panic—

Three execution poles were erected on the riverbank. To this day I don’t know if they were ever used because early the next morning American jets from carriers off the coast destroyed the North Vietnamese forces surrounding the city.

But I couldn’t forget what I’d done in ordering that firing squad.

I knew that America’s war was wrong. I knew the US was losing. I knew that those deserters were mostly innocent farm boys kidnapped by the army off their rice paddies only weeks or months before, given little training and scared out of their wits.

And yet I’d been a willing partner in this violence, and for the shallowest of reasons. Adventure and power. At least with tribal or political violence there’s a sense of supporting your own group. I did what I did in Vietnam only to please myself. My ego drove the narrative of my life then.

I thought about and agonized about my role in Vietnam for a long time.

Slowly my life began to change.

Promotions kept coming.

But what I was doing and why began to sit in my stomach like a bad meal.

You see, mixed in with all these adventures, all the tough guy stuff I was doing, was a set of dreams, of ideals—about peace, about fairness in the world, about ending the suffering caused by wars and revolutions and poverty. It was the beginning of a new narrative for my life but it was only a small, nagging voice from my heart and I ignored it for many years.

Then came a turning point--

In 1977, I was transferred to the US Mission to the United Nations as an assistant to Ambassador Andrew Young. Part of my job there was to represent the United States on the Security Council Committee that dealt with South Africa and apartheid. That committee was supposed to enforce a UN arms embargo on South Africa. It had been imposed because guns sold to the South African government in those years were used to enforce apartheid—to kill blacks. But the embargo leaked like a sieve. Why? Because there were huge amounts of money involved in the arms trade, and the arms dealers had their friends in parliaments in Europe and in our own Congress.

I ignored my instructions to not make waves and instead worked secretly for months to tighten that embargo. I did that by helping Third World countries increase their pressure against my own government. Once our Secretary of State received a strong message from an African Foreign Minister complaining about American hypocrisy over the arms embargo. In it, I recognized words that I myself had drafted two weeks before, given to an African colleague at the UN—who had sent it to his Minister.

Then I went to my bosses and remarked on the huge upsurge of pressure coming from the Third World to tighten the embargo, and the enormous pressure being put on the US government to live up to its promises—pressure that I myself had helped generate. It worked. The US agreed to a really tough embargo and the Europeans had no choice but to follow suit. On May 2, 1980, that embargo was passed by the Security Council and, in time, it helped end apartheid.

At any time in this process I could have been fired.

Why did I do this? Why did I take these risks?

I did it because of one day spent in South Africa. The day began in the squalor and oppression of the black township of Soweto. I walked down garbage-strewn streets. I felt the hate-filled eyes of hundreds of young black men boring into the back of my white head. The day ended with a diplomatic cocktail party in Johannesburg’s fanciest white suburb, in a mansion surrounded by iron fences and guard dogs.

Apartheid stank and I resolved to do something to end it.

At a deeper level, I took those risks because helping end the injustice of apartheid meant something to me at the deepest place in my soul, something more than adventure or power.

It was, however, not lost on me that I had just had the best adventure of my life and it had nothing to do with dodging bullets or hanging off a cliff by a rope.

The experience was like learning to swim.

I couldn't forget what I’d done.

I couldn’t forget how to do it.

I couldn’t forget the joy and fulfillment I felt in making a difference like that.

I’d found the meaning for my life and, like Giraffe Heroes, I’d found it in service, in bettering the lives of others, in helping solve a significant public problem, in building peace instead of war. I finally accepted the new narrative for my life.

Since then, I’ve watched many other people make the same discovery. Watched them find meaning in service, in bettering the lives of other people. Watched them form new narratives.

Watched them use those narratives to fuel their commitment and energy to take on tough tasks and succeed—and to experience the satisfaction of living their lives to the fullest.

What’s been true for me and true for Giraffe Heroes is or will be true for you. I guarantee it.

It doesn’t matter if your service is big or small. Every one of us has and will have unique opportunities to make a difference in our communities and in our nations.

This year’s election campaign in Ghana will provide many for you. What can you do to help keep it free, fair and nonviolent?

A successful life is about spotting those opportunities and acting on them.

The only mistake you can make is to ignore the quest, to live and die without every having made a difference.

Here’s the story of two people in northern Nigeria who took on that quest:

Imam Muhammad Ashafa and Pastor James Wuye are religious leaders who live in Kaduna, northern Nigeria. Today, they work together to teach warring religious youth militias to resolve their conflicts peacefully. But they did not start out as peacemakers. Twenty years ago, Imam Ashafa and Pastor James were mortal enemies, intent on killing one another in the name of religion.

In 1992, violent interreligious conflict broke out in Kaduna State. Christians and Muslims fought each other in the marketplace, destroying each other’s crops and attacking each other’s families. Both the Imam and the Pastor were drawn into the fighting, and both paid a heavy price for their involvement — Imam Ashafa with the loss of two brothers and his teacher, Pastor James with the loss of his hand.

They each dreamed of revenge against the other. Nonetheless, as leaders in their communities, the two men reluctantly agreed to meet. Over the next few years, the two men slowly built mutual respect. A key part of this was forgiving and asking forgiveness from the other. They began to work together to bridge the divide between their communities, mediating between Christians and Muslims throughout Nigeria. Their organization, Interfaith Mediation Centre now with over 10,000 members, reaches into the militias and trains the country’s youth—as well as women, religious figures, and tribal leaders—to become civic peace activists. Under their leadership, Muslim and Christian youth jointly rebuild the mosques and churches they once destroyed through war and violence.

The Imam and the Pastor have since expanded their work, for example in helping quell tribal violence after violent elections in Kenya in 2011.

Their work is not about crafting clever political solutions but about convincing enough people on either side of the conflict to go deep inside and look at their own motivations for fighting. What is missing in their own hearts? Would spilling more blood bring meaning to their lives? Or would taking the risks to forgive, and to build peace?

The Imam and the Pastor are helping build a new narrative for their country and the world.

I’m here in Ghana to help Nana Darkwa and others launch a powerful program to help build that new narrative here. It will be called Giraffe Heroes Ghana. It will find men, women and youth in Ghana who are acting with courage and compassion to build peaceful, just communities and nation--people who are writing the new narrative here with their lives. And it will tell their stories far and wide, inspiring and guiding many more Ghanaians to become part of this new narrative too.

So here’s the take-away from this talk. The answers to violence can’t be limited to security forces and stable institutions although those are important. The problem is just too deep for that. We need a whole new brave and compassionate narrative to replace the narrative that now feeds on corruption, grievances, ignorance, fear, economic injustices and bad leadership. A new narrative based on individuals and nations finding a deeper meaning for their existence, one based on service.

And while this afternoon I’ve talked mostly about Ghana’s internal situation, much the same strategy, in my opinion, must be used to destroy the power of radical Islam to attract angry young men. Their old narrative must broken and replaced.

Peacemaking is hard.

Standing up to say hard truths and to do hard things when you have to is not only hard; it can be dangerous.

Taking personal responsibility for the changes you want to see in your communities in nation is hard, including fighting corruption and economic injustice wherever you see it.

Creating a compelling vision for others to follow you into a new narrative is hard.

You lead at whatever levels you are called to lead, in your community, at your place of work, in your nation.

What role is there for you, specifically you, as an agent of change? Only you can know that. You lift up that corner of the rug you can reach.

The American poet Mary Oliver asks:

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

What a question!

It may be the most important question any of us will ever ask.

Never give up the search for meaning in your life and never settle for anything less.

Ask what you can do with your talents, your experience, your resources.

Find the challenge or problem that you care about, the one with your name on it. The one where you help build a peaceful and successful nation.

Then take this challenge on.

This is your new narrative.

As you do this work, with your one wild and precious life—

Do it to help solve the problem.

Do it to help make your country and the world a better place

But also do it for you—for the joy and fulfillment of living a meaningful life.