Denali Diary Part Two

—the Adventure Continues

If you haven't read Part One, you can find it in the NAV bar. Part One takes the story up the AlCan Highway to Alaska, past the Russian Roulette we played with massive avalanches, up and over steep rock, and, finally, threading our way past a massive ice cliff that marked the end of the hard technical climbing.

The dangers described in Part Two were different, focused on surviving Denali's vicious weather—and the fast-moving currents of the McKinley River.

CHAPTER FIVE: ON TO THE SUMMIT!

10,400’ was an important transition point on our climb. Now the air was cold enough for us to switch from climbing at night to climbing during the day—no steps were going to melt out. We will do that by climbing from the night of July 6-7 straight through until the following evening.

10,400 feet marked another important milestone on the climb. “The Icebox” at 10,300’ turned out to be the last bit of significant technical climbing on our route. From here on, there were no more rock faces to climb, we could end-around any ice cliffs and the slope up to the North Summit gentled to an average of 40 degrees. The challenge now was to thread our way up through ice blocks and crevasses. While the footing was easier up here, the snow made for hard and exhausting slogging. We were also beginning to feel the altitude a bit which slowed us down. And, as we were about to be reminded, the weather on Denali is always a potential serious threat.

July 6

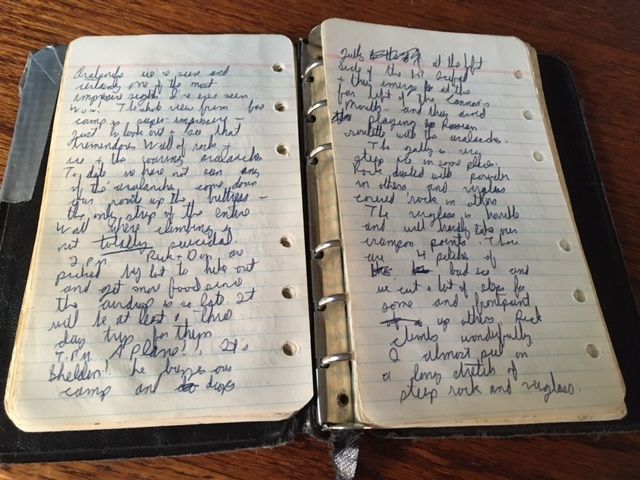

We begin at 3:00 AM, shuttling loads from Camp 4 to Camp 5 and then to the cache at tentative Camp 6. The stretch up from Camp 5 is fantastic ice scenery: huge ice cliffs, jumbled seracs the size of hotels and fields of broken ice blocks. All in all, the night is easy and uneventful and we all return to Camp 5 to pad about 9 AM.

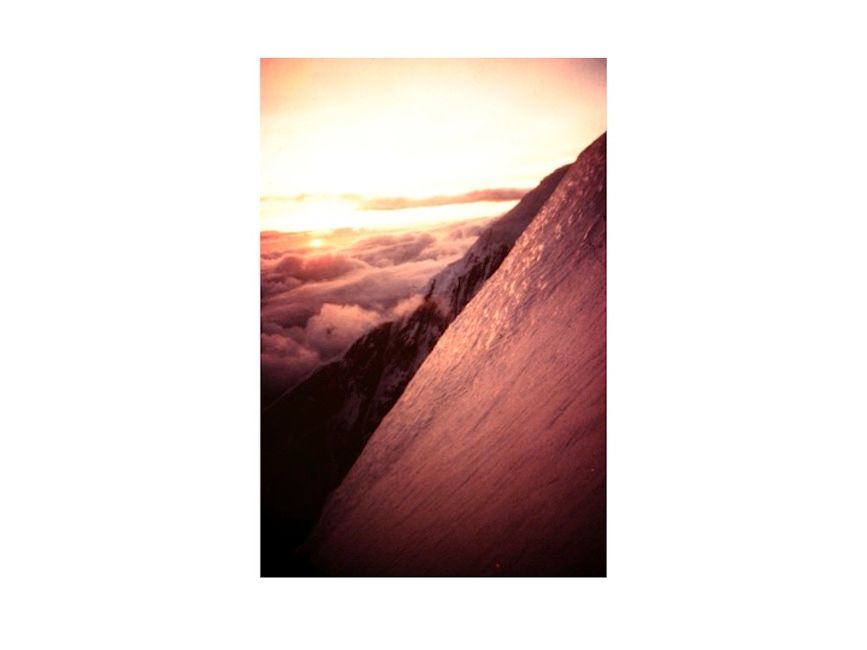

The evening of July 6 is the start of a memorable marathon. We eat at 8 PM and then strike Camp 5 and move to tentative Camp 6 and set up the tents. Everything is now at tentative Camp 6. The view from here is tremendous, especially sunrises and sunsets which are practically impossible to tell apart up here.

Chris and Dave have reported that the going was fairly easy above tentative Camp 6 so we do not bother to send out route-finders but we all rope up and head up together. Our plan is to go until we just can’t go no further. Our route above tentative Camp 6 twists and turns up through a maze of ice cliffs and seracs. Most of it is on 30-50° hard snow with a few ice pitches. We've all got summit fever now. We take 55 pound loads and really roar..

July 7

We climb steadily. At 6 AM, pushing hard, we establish a new cache at about 12,600 feet, which becomes the new Camp 6.

Good news. The lead team reports that the top of the Wall is almost in sight.

Clarification: officially the term “Wickersham Wall” refers to the entire north face of Denali from the Peters Glacier at 5350’ to the North Summit at 19,470.’ However, my diary notes suggest that we on the team, for some reason, considered the top of the Wickersham Wall to be the point where only steep snow climbing remained on our path to the North Summit—that is, somewhere around 14,500—the same altitude as the ice cliffs to the left and right of our route that generated the mighty avalanches that threatened us at the ”Cannons’ Mouth,” now far below.

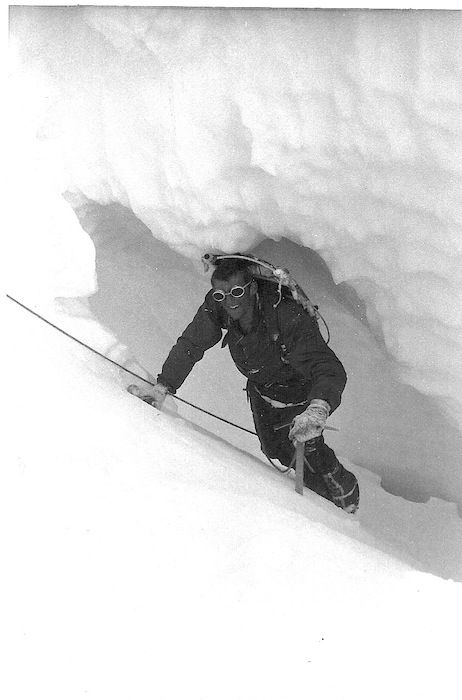

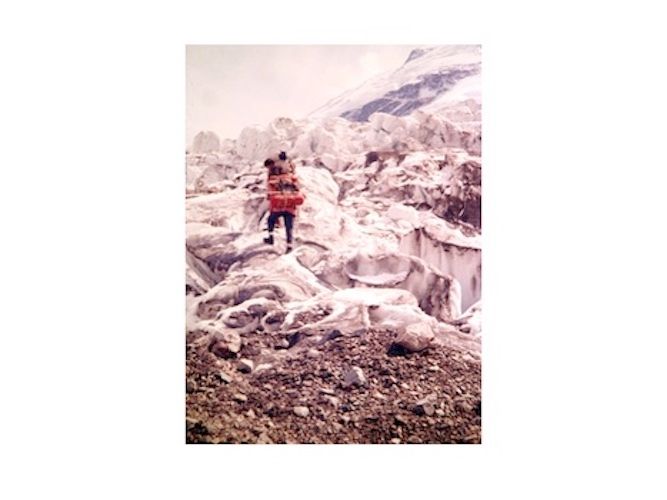

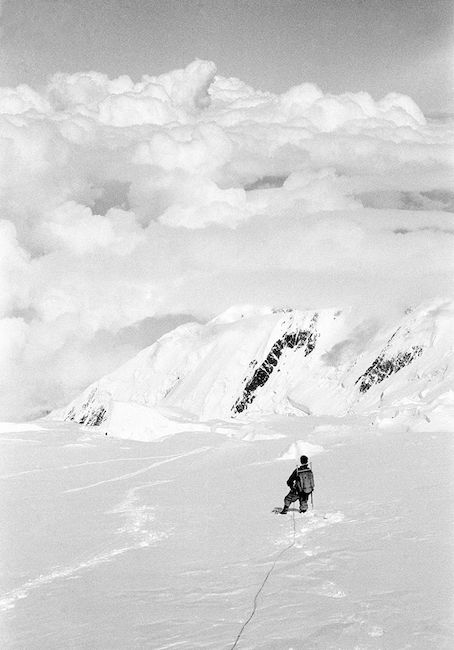

Just above the ice cliffs

Packing to Camp 6 was hard slogging. And it would get worse as the air got thinner..

The weather looks definitely like snow now however. Rather than take the chance of having to re-break the trail from tentative Camp 6 to our new Camp 6 we elect to return to tentative Camp 6 and strike it, moving everything up to the new Camp 6. It is really the only choice although we realize that it will call for a superhuman effort on everybody’s part. We return to our tents at tentative Camp 6. The way down is largely a glissade and I come close to killing myself again. On one glissade I miss a snow bridge and catapult myself headfirst 30 feet down into a crevasse (which I climb out of unhurt). Another time I lost control of my glissade and narrowly escaped being badly cramponed. Both times were due to obvious errors of judgment on my part but they were still damn fun.

We have a huge meal at tentative Camp 6 and at 11:30 AM start the haul to the new Camp 6 at 12,600’. We make it by 5 PM, so tired we can hardly stand. It begins to snow and we crawl in our tents. Everything is now at Camp Six. We are near the top of the Wall and the North summit may be only 3 to 4 days off now. The snow picks up. It had been a truly grueling day: 55-60 pound packs, carried up 5,600’ total altitude.

We sleep all through the night. What a blessing! We are all damn worn out and badly in need of a night’s rest.

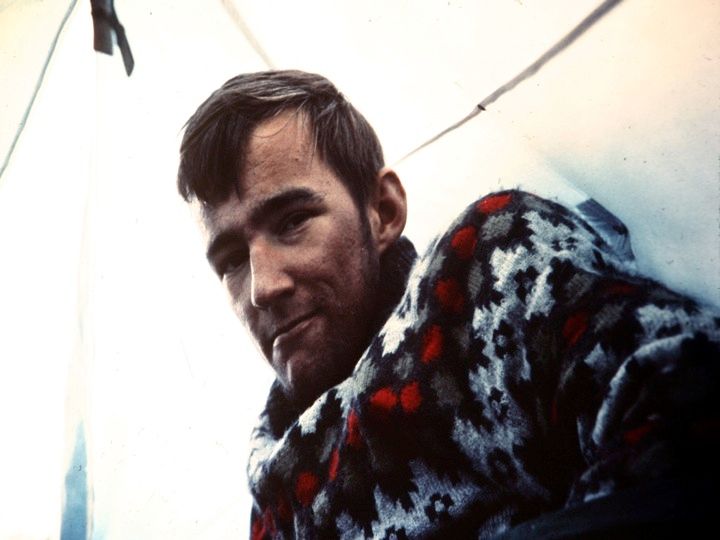

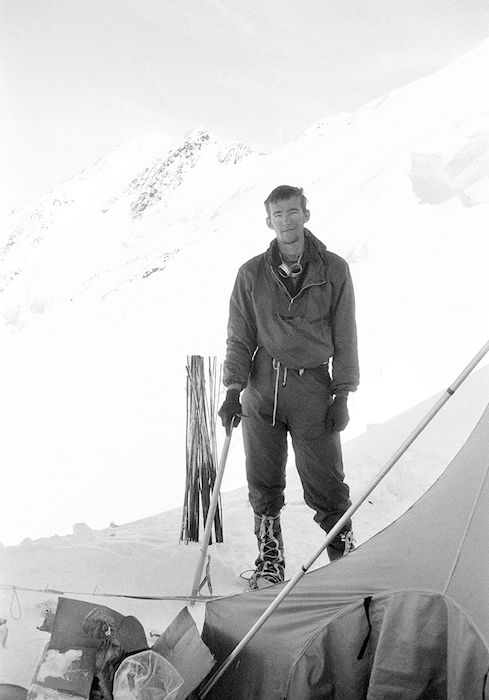

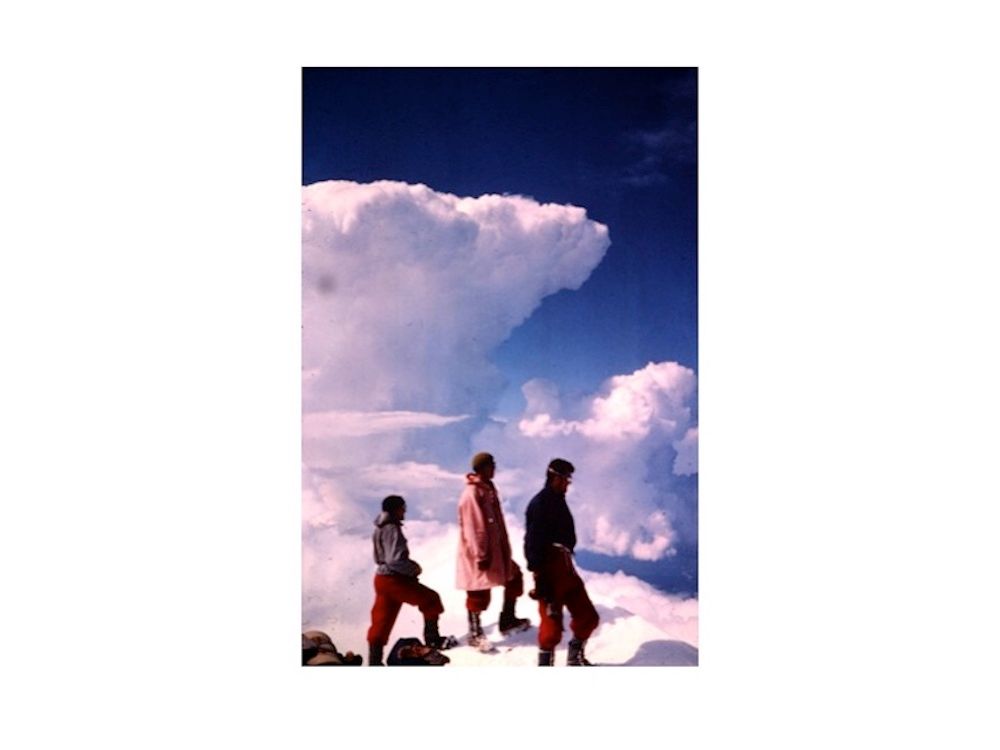

Carman, Roberts and Jensen at Camp 6

Roberts and me at Camp Six

Roberts, Jensen and Carman on top of the world

Ominous clouds

July 8

At this altitude I find I must make an extra effort breathing and end up panting a few times. Chris and I are the cooks for this stint and kerosene fumes make him ill part of the night. We fix the faulty Primus stove the next day.

The morning dawns still snowing. I for one am not disappointed. We’ve been pushing ourselves like madmen since we left Basecamp and have made incredibly rapid progress. What’s left will call not so much for technical skill but sheer endurance. I think we all feel better with a rest day before we go over the top. We’re now back on a day-night schedule since it is cold enough up here to make snow conditions stable and daytime climbing not excessively warm.

We plan to establish one more camp as high as we can (about 15 or 16,000’) before we light out single-packing for the North Summit. Most of the day is spent in our two-tent hotel, reading aloud from a novel.

As I remember, our favorite was the Northwest Passage by Kenneth Roberts. In fact, we tore the book into seven pieces and each read one of them aloud, not necessarily in the right order, while the others offered sound effects and irreverent commentary.

A straight shot to the North Summit!

The weather clears momentarily giving us a tremendous view. We are camped among huge seracs at the edge of a great ice cliff. Below, only the top of Peter’s Dome to the north sticks up from a blanket of thick cloud, giving an impression of great height. The snow soon resumes and the readings take up again. By nightfall, the storm has increased.

July 9

Morning clouds and windy. Chris and I get breakfast ready at 4:30. Today is a real work day. We each carry two loads up to a new camp site (Camp 7) at about 14,500, virtually at the top of the Wall. The going was a bit slow because of a lot of deep powder. The weather is getting fiercer with the height. Steady wind. Temperatures around 15 to 20°. After a glop meal, we all pad, really tired. A snowstorm has come up. Down in the valleys, thunderheads are forming below.

Below—shots of the relatively easy going just above Camp 6.

.

Below—two shots of Camp 7, 14,500'

.

The shot below looks due west from Camp 7 at 14,500,' at the top of the avalanche chute that became the Cannon's Mouth lower down the face. And they all missed!

Good mornin' sunshine—from about 16,000

July 10

More double-packing. Weather perfect. Temperature is from 12 to 25°. All that’s left now is the long slog. We can see the North Summit above us. Altitude and deep powder slow us down. We pitch Camp 8 at about 16,100 feet, directly below the North Summit. Don, Dave and Rick take small loads up another 700’ and cache them while the rest of us hack out a platform for the tents on the slope.

Pete and I have altitude headaches for awhile. Now we have only high altitude food. We gorge ourselves on low altitude lunch goodies from Camp 7.

The going remaining will be physically damn tough but no technical problems or avalanche and rockfall dangers are left. Packing at this altitude is an awful masochistic business: kick steps, pant, kick steps, pant…I’ll be glad when we’re there. Two more days should do it (with good weather). Had a victory cigar this afternoon when it was obvious we had topped the Wall. I thought we heard Sheldon buzz us but it was not him. Maybe he’s missed us. Nobody expected us to be this high this soon (least of all ourselves).

July 11

We spend the whole day packing from Camp 8 at 16,100’ to Camp 9 at 17,400.’ The going was awful. Up a 40° slope of powder overlying ice. The altitude no longer seems to bother me but Hank was sick most of the day. Breaking trail is sheer hell: step, kick pant… Hank, Rick and Dave double-pack part of the way.

Camp 9. My diary does not begin to explain what it felt like at Camp 9, perched precariously on a platform we'd hacked out of the ice on a 45° slope at 17,400,' secured to the mountain only by a few aluminum pickets and stakes. But it didn't get really scary until the storm hit and we realized how vulnerable we really were, trusting that the stakes wouldn't pull out and we'd roll down thousands of feet or that the nylon fabric protecting us from freezing wouldn't shred in the blizzard. Here are three pictures taken just before the storm arrived.

From Rick Millikan’s account: "July 11 was not a good day. We all were beginning to feel the altitude. At worst we would take 10 steps and then sit down for five minutes; at best we needed one or two deep breaths between each step.We were going very slowly. The summit seemed so close but after three hours it seemed no closer. At 17,400 feet we reached a rock outcropping above which was a somewhat less steep stretch of snow. After two hours we had hacked away a platform big enough to squeeze our three tents on.".

July 12

Temperatures near zero with gusty winds. By afternoon this improves a bit and all but Hank and I take light loads up to a cache at 19,100 feet. The going is reportedly tough—altitude, weather and lousy, treacherous snow.

July 13

The storm worsens. We all stay in our tents at Camp 9. Temperatures near zero. We are fairly warm in the tents but outside is bad. Even relieving oneself means risking a serious chance of frost bite.

It seems important to expand on this point since so many people keep asking me about it. Trapped in our tents, relieving oneself requires some planning and effort. The person needing to go ropes up with a flimsy belay anchored by wrapping the rope around an ice ax jammed into the snow just outside the tent. The person doing his business crawls out of the tent onto the tiny tent platform hacked into a 40° snow and ice slope in a snowstorm, then jams a second ice ax uphill as hard as he can. Peeing requires being as careful as possible not to let pee blow back into the tent. Going “Number Two” is far more of an adventure. The person leans back over thousands of feet of space with only his ice ax for support, hangs on for his life, and does his thing. There was never an accident but plenty of occasions for potty humor. I remember the fun we had composing letters we might have to send to next of kin in event of an accident e.g.: “Dear Mr. and Mrs. Roberts, your son David crapped out at 19,000 feet"

July 14

Storm worsens. Dammit! It is sheer hell being penned in our tents only less than 2000’ from our goal. It is almost impossible to muster the patience necessary. The temperatures are still near zero with winds as high as 50 mph. Outside, without protection, we would be dead in minutes. Visibility clears intermittently and several planes buzz us. We can’t be sure if we’ve been seen or not.

We keep reading and play-acting from Northwest Passage. There is really nothing else to do.

We have enough food and fuel to wait out a few more days before we would have to go up to the cache at 19,000 to resupply. I’ll be damn glad when we’re down to safe altitudes again. Even a slight misstep or accident up here and we are in real trouble. Here, above the Wall, where we thought the going would be easy, we are encountering our first really bad obstacle. Hell.

I thought it interesting that I wrote that the storm was “our first really bad obstacle” considering everything and we had gone through before. I think it reflected the strain we all felt and perhaps the fact that our previous obstacles had all been climbing obstacles: falls, avalanches, rockfalls, collapsing cornices, crevasses... Being wiped out in a storm somehow seemed different, and worse.

July 15

Storm continues. The morning shows a slight break and we all get on our climbing clothes. After breakfast everything socks in again, the wind comes back and we all retreat into our novels.

This is the really frustrating aspect of mountaineering. Stormed in at 17,400 feet for five days on a 40° slope where leaving the tent to urinate could be fatal ( but boy wouldn’t that be ironic!)

We are still all in pretty good spirits but there is a noticeable mental as well as physical strain to our precarious position. We are right smack in the middle of the north face, albeit above the special dangers of the Wall but absolutely at the mercy of the weather. We must be very careful. But boy is it great to be snuggled into a warm bag and listen to the wind thundering like an express train.

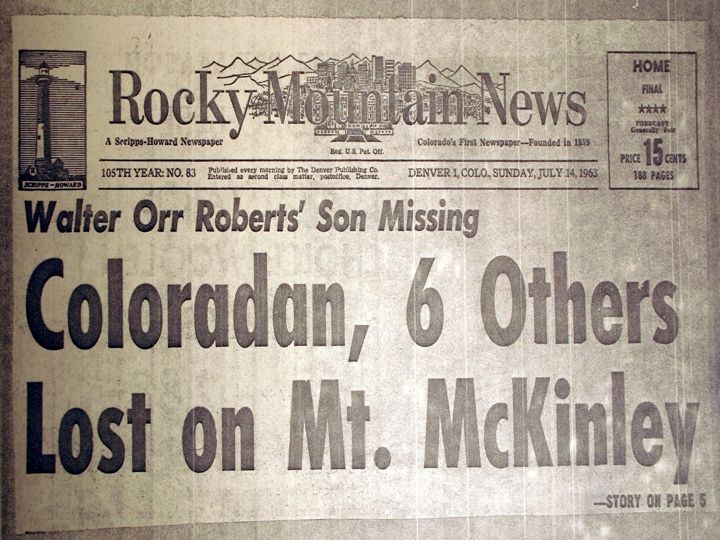

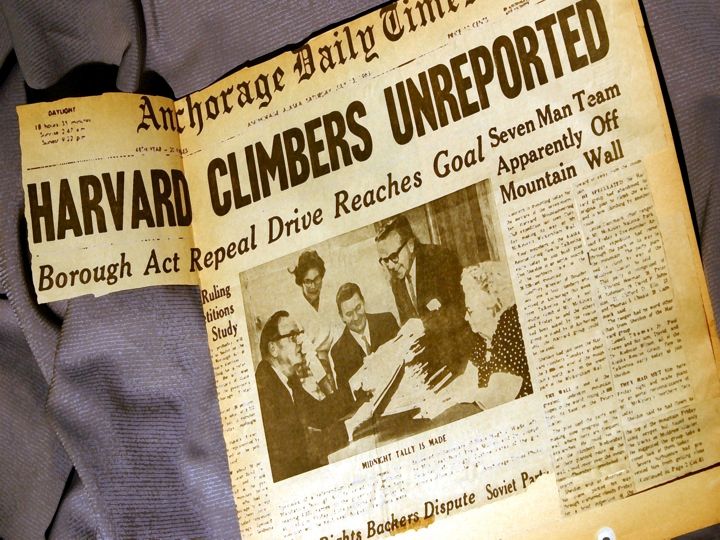

As noted earlier, trapped in our tents, invisible in the blowing snow, with no means of communication to the outside world—we had no idea that for these five days at Camp 9 we were a global news item. When Huntley-Brinkley Nightly News told Americans we were feared lost, many people believed them. But we had climbed this high 4-5 days ahead of "schedule," (whatever that meant), and efforts by search planes, when there was enough of a break in the weather to fly, searched too low. They saw our lower route buried in avalanche debris and drew the worst—and wrong—conclusions.

July 16

It downs bright, almost clear and windless. We all feel that this is the day. We rise at 4:30, eat a great pork chop and scrambled eggs breakfast and strike camp at 7:00. Up we go. The altitude wears even more but five days at Camp 9 have helped us a lot.

Our first objective is the cache at 19,100 feet. The weather does not remain perfect and soon it becomes down jacket weather. Pete and Dave complain of cold limbs but there is no frostbite. We go up a 40° snow and ice slope. We finally reached the cache at about 1 PM. Our gung ho outfit elects not to stop and camp but to add the cache load to the loads already on our backs. Ugh. I figure I’m carrying about 55 pounds. The weather turns very bad just a few hundred feet below our goal.

We make the North Summit at about 3:30 PM, July 16—26 tough, exciting days since Base Camp.

From Hank Abron’s journal:

“The crusty snow broke beneath us as we cramponed under anklecracking 50-pound loads. Stopping frequently to rewarm our feet, we reached 19,000 feet by noon. The weather suddenly looked dismal, and the lead rope disappeared into the mist like Mallory and Irvine. It was agony to look ahead, for particles of ice blew straight into our eyes. We literally hugged the ridge, straddling it with our knees and gouging it with our heels, for in the wind it seemed to buck under us like a horse.

Proudly, we reached the top and stood congratulating each other and thanking Lady Luck. Then, our exultation tinged with amusement at what we had so brazenly done, in a note in a bottle tied to a rappel picket, we signed our names under a quotation from Bradford Washburn: "… One of the greatest precipices known to man.”

Temperature is -5° and wind velocity at 55 mph. We manage a few pictures. We have done it. I fail to light a victory cigar on the summit. Sob.

We have climbed an arrow-straight route up the center of the North Wall. We have done what everybody said would never be done. Boy do we feel good.

Right now of course we are in real trouble. We rope ourselves close together and stumble down the opposite ridge. Pete takes a fall.

I thought I’d become immune to the altitude but I was wrong. Pete and I were together on a short rope. He goes first but because the visibility is less than 25 feet he soon disappears into the storm. I know he’s moving because I can see the coil of rope at my feet move. But suddenly the rope starts flying off the coil—zip zip zip. Lightheaded from the altitude, I momentarily don’t react. Hank yells at me just in time for me to snub the rope around my ice ax and arrest Pete’s fall. He climbs back up to the ridge and continues down.

We give up any hope of trying to get to Denali Pass this day and are lucky to find a flat semi-protected spot to make our camp. Our beards are covered in ice and our eyelids are almost iced shut. We are lucky. We are also totally exhausted. Days like this one are what made us successful. We are capable of putting in superhuman days when we have to. Today was really tough. I would not like to put myself in a much worse spot

Victory dinner tonight: extra Starlight freeze-dry and coffee. We are in a great position now to bag the South Summit whenever the weather clears. What a relief to be off that #!@ Wall. We are camping on almost level ground. And even kids and ladies have gone down the West Buttress route which will also be our route of descent.

Coming up that last hundred yards to the North Summit was perhaps the hardest going of the trip. It was almost complete white-out and high winds. We had to climb with packs up a knife edge ridge and I swear I was forced to do some of it on my hands and knees, jamming in my ax and pulling myself up.

Boy it is hard to express the comfort of living in these double-wall tents. It is not so bad here but when the storm was really howling on the North Face those bits of nylon plus our down bags made a really swell refuge from truly killing conditions.

This has been one of the most satisfying days in my life

The victory dinner pot overturned and partially ruined the meal but Don’s victory liqueur saved the occasion.

CHAPTER SIX: THIS TALE ISN'T OVER

July 17

Woke at 11 AM and had a big, leisurely breakfast. Conditions outside are slightly snowy, visibility poor, no wind. We should really push on to Denali Pass which is the best attack base for the South Summit [Denali’s true high point]. We rationalize our way out of it, however. We certainly wouldn’t want to climb to the South Summit with this visibility and we figure Denali Pass is only two hours off and our camp here is comfortable so we pad, read and goof off for the day. The talk is already turning to winding up expedition costs, handling publicity etc. All of us, especially me, are dreaming of a huge steak dinner.

With a body significantly bigger than anyone else’s on the team, I had a significantly bigger appetite. But in Scarsdale we figured meal portions as equal shares, meaning that I was hungry for most of the trip, even with occasional kind supplements from my friends. And before we left McKinley Park on our way in, the manager of the McKinley Park Hotel, sharing the widespread belief that our climb was suicidal, made a public promise that he would feed us all the steak dinners we could eat if we made the climb and survived. Now it was pay-up time!

July 18

Rose late because socked-in conditions forbid a summit try. About 1 PM we strike camp and head for Denali Pass. Weather cold but no wind and visibility improving. We find an easy way down over a rock ridge and reach Denali Pass. Behold four other climbers! They had come up the Muldrow [Glacier] and will do the North Summit tonight. We’ll all do the South Summit tomorrow and then head down the West Buttress. These four are the only human beings we have seen for over a month.

Weather clears. Magnificent views especially of Mt. Foraker and the South Summit. Temperature at 6 PM is -19 Fahrenheit.

July 19

Breakfast at 7 AM and then we wait out a blustery morning. Early in the afternoon it clears and we head for the South Summit. We do it unroped in about 3 ½ hours.

North Summit from near South Summit

Dave and I are the first up. We hug each other for joy. We’ve done it! The weather is clear, temperature -12 Fahrenheit. We take lots of pictures. What a view. We are on the highest point in North America, way above a distant cloud layer. Still there is no doubt that the South Summit is an anti-climax after topping the Wall. It was just sugar on our cake. Our adventure has been amazingly successful and now it is all but over. We have a big victory celebration tonight.

July 20

Chris and I whip up a breakfast and we all are up to watch the total sun eclipse around 10 AM. Then we strike camp just as two of our new climbing neighbors come into view after camping on the South Summit.

Total eclipse from Denali Pass

Our route down starts with an easy descent from Denali Pass down the West Buttress route, glissading much of the way to the Kahiltna Glacier at the mountain’s base at about 7,000.’ Ah, the thick air! Then we will begin circling clockwise around the mountain, climbing over Kahiltna Pass and onto the Peter’s Glacier to our starting point at our original base camp. The only tricky part of this is the Tluna Icefall, an area of broken ice and crevasses where we will need to be careful. In fact, we do fall in a number of crevasses but we are roped up and easily pull each other out without incident.

We head down the West Buttress [the standard route up Denali]. Weather absolutely magnificent. We find caches abandoned by previous expeditions all the way down and gorge ourselves on goodies—peanut butter, jam, crackers…Views are fabulous. Climbing is easy and fun.

We leave a ridge and glissade down toward Windy Corner. Great luck! We find a tremendous old food cache and camp there about 5 PM. We feast on beef steaks, potatoes, coffee, lemonade etc. I light up a cigar. We are about 14,700 feet. Temperature is +19 and it is clear and windless. We sit outside and read books and a copy of the Wall Street Journal given to us by the other climbers. We take pictures. Oh the soft life!

July 21

We get up at 2 AM so as to get the best snowshoeing conditions on the glaciers below. Going is good except I discover I have a partially sprained knee and as the day goes on it becomes quite painful. But on we go, sometimes on snowshoes, sometimes with crampons. We go past Windy Corner, then reach Kahiltna Pass. At about 11 AM we reach the Tluna Icefall and start to pick our away gingerly across, falling in crevasses as we go. The snow is becoming not so firm. We reach a moraine and follow it for a while, then we cut back onto the bottom part of the Icefall. What a place! Fantastic ice forms and seracs rearing in unbelievable fashion. I’ve never seen anything like this before.

I managed to slash my little finger and have a second nosebleed before we are through the Icefall. Good thing we are almost home!

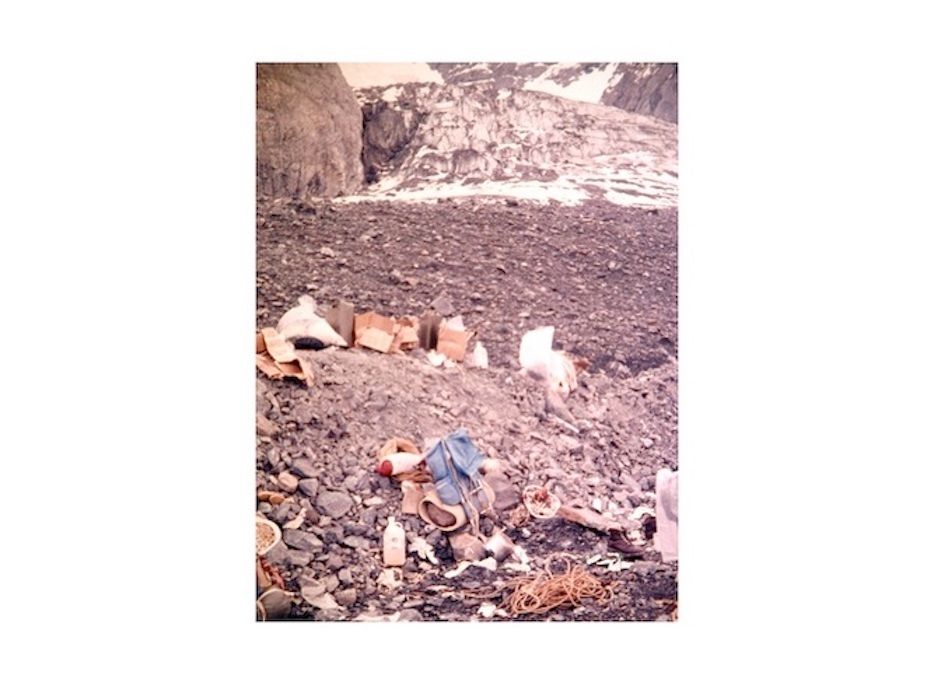

Four shots of the Wickersham Wall as we hiked down the glacier at its base, back to our original Base Camp.

How the hell did we ever get up THAT?!

In his Alpinist interview, Dave Roberts describes the unique combination of fun and danger that marked this trip: “This is a great, fun vacation," he told Alpinist, "and even the setbacks were part of the good times. There was a lot of raucous cajolery back and forth. We actually had a fair number of what I would now regard as close calls that were potentially pretty dangerous: falling rocks and avalanches. On the summit day on the north peak, Pete Carman fell off the summit ridge. Again, we just treated it like a joke. Going through the Tluna Icefall on the way back to base camp was also really dangerous. Three or four times we went in up to our chests in crevasses..."

On we go, closer and closer to the site of our original Base Camp. We make it by afternoon. More orgy! Cans of fruit cocktail we had left behind go down like water. Yum.

Base Camp is completely changed. Most of the snow is gone. Once again, we hear the sound of avalanches but all they do now is invite indecent finger gestures from all of us.

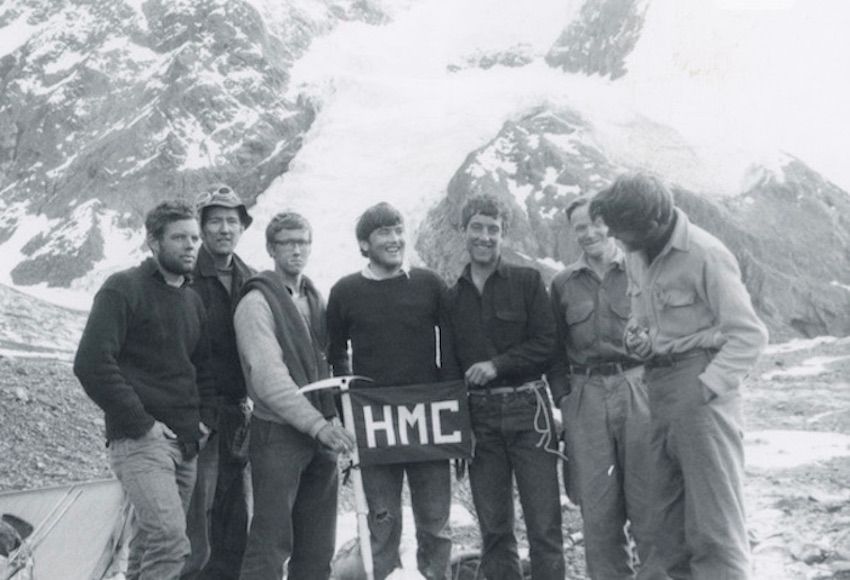

Gaunt, tired and happy

July 22

We gorge ourselves some more on Base Camp goodies and leave about 4 PM. The snow is gone from the glacier and we must wind our way over the moraine. Tough going. Weather is overcast and it rains some. Finally we are off the glacier and onto a bench. We camp about 11 PM on soft grass.

July 23

Up at 8:30 AM, off by 10. Soon we are encountering muskeg bogs. My knee begins to hurt badly and Hank tapes it. We cross Carlson Creek. More tough going. Heavy showers. Crossing Clearwater Creek is not bad, then more lousy going plowing through horrible swamps in the rain. Finally we see the McKinley River and about 9:30 PM we arrive at its banks, very tired.

From my memoir, Quest:

“When we reached the McKinley River, we could see our bus on the far bank, a half-mile away.

The water level in rivers like the McKinley varies dramatically, depending on the time of day. Sunlight had hit the north side of the mountain in the morning, melting the snow and ice. That evening, the meltwater was roaring past us in full flood. There’s a prime directive in crossing dangerous, glacier-fed rivers—wait until low water. But that would have required patience we did not have. We roped up and headed across.”

NOTE: at this point and time the McKinley River consisted of 11 channels and altogether was about half a mile wide.

The river is high and dangerous but we decide to rope across. Hank and I are on [the last] rope. I go down in a middle channel but am held, thank God. Now I am wet through. On the last channel Hank goes first and reaches the far bank. I try to follow but I step into a bad place and immediately I am swept off my feet and fight to keep from drowning [with Hank now sprawling on the riverbank]. I pendulum across the torrent.

More detail from Quest:

“Tons of fast-moving water pummeled me against rocks on the stream bottom. Swimming was impossible. Hank was pulled off his feet by the rope that joined us, and was being dragged backward across the gravel toward the flood. The others were too far away to help in time. In the next 30 seconds, either the pull of the rope would pendulum me onto the far bank, or the force of the river propelling me downstream would pull Hank in, too, and we both would drown.

“Hank spread-eagled himself on the bank, desperately trying to resist the pull of the rope, but there was nothing to hold on to and he was pulled foot by foot closer to the edge. I was helpless, one moment smashed against the rocks on the river bottom, then up, gasping for air.”

Finally I can crawl on my hands and knees but the terrible force of a current leaves me almost powerless to move. But it is literally do or die. I do not die.

I hit the far bank seconds before Hank was dragged the final few feet into the river. Moments later, the others pulled us both to safety. We stagger out shivering and exhausted and collapse on the far bank.

Only one last bit to go. Never have I felt less like pushing myself. As far as I am concerned. I have just come closer to death than I have ever come before. It would have been worth it to pay Sheldon for a pick up. Near midnight I stagger onto the road with the others. Some wag has changed the taped sign on the side of our VW bus from “Harvard” to “Yale,” but everything else is intact. Our words on seeing the car are ecstatic. Thank God. Thank God. We have made it.

We drive to the Eielson visitor center, change in the restroom, cook a glop and sleep.

July 24

We drive to McKinley Park. We find out soon enough that we are celebrities; we were thought missing and followed by the national press.

My diary ends here so I will continue with this description from Quest:

“Next day, we reached the McKinley Park Hotel to collect on a bet: the hotel manager had made a public wager that if the Harvard team climbed the north wall and lived to tell about it, he would treat us to all the steak dinners we could eat. The meal turned out to be even more dramatic than we’d expected. Unbeknownst to us, three weeks before, a bush pilot had reported seeing our tracks disappear into avalanche debris, and “Harvard Climbers Missing” had turned up on front pages all over the country. Hopes for us had “dimmed” when that four-day storm had hidden our tents, just beneath the north summit, from view. Once the storm cleared, our tents were sighted, but good news travels more slowly than bad. When the seven of us tramped into the dining room of the hotel—gaunt, unshaven, red-eyed, sunburned—a few astonished patrons looked at us as if we’d returned from the dead—a reaction duplicated by more than a few friends in Cambridge that fall.”

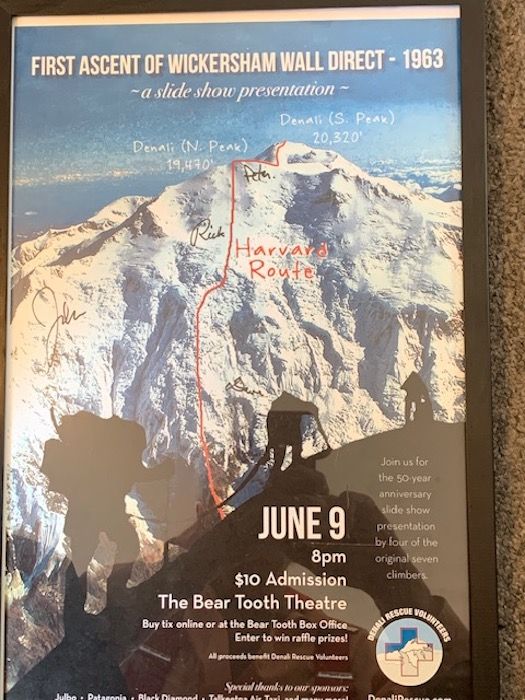

CHAPTER SEVEN: FIFTY YEARS LATER

In July 2013, four of us from the original Harvard team journeyed to Alaska to celebrate the 50th anniversary of our climb. Our only regret was the absence of Hank, Chris, and Don. Hank couldn’t make the trip and Chris and Don had both died young, but neither one from mountaineering.

Dave Roberts, Rick Millikan, me and Pete Carman

Reminiscing over beers, we four agreed that our 1963 climb had “worked” in part because of how smoothly we’d functioned together as a team of equals. And we were all delighted that the camaraderie that had supported us so well 50 years ago reappeared, it seemed, in minutes, even though some of us had not seen each other for decades. We all remembered how that intense adventure, with our lives in each other’s hands, had welded us as a team a half-century before

In fifty years, the “Harvard Route,” unrepeated, has become one of the most iconic climbs in North American mountaineering, especially in Alaska where many people know the story. So the halls were full in Anchorage, Talkeetna and Wonder Lake for the public presentations we gave of our 1963 slides.

The hotel at McKinley Park had burned down years before, so there was no chance for a reprise dinner. As another part of our reunion, however, the four of us hired a bush pilot to fly us by the Wall. There was remarkably little talk as we stared at the massive face, its cliffs and towers looking as fearsome as we’d found them 50 years before.

At the Q&As following our slide shows, one question kept coming up: “Did this experience change your lives—and how?”

All of us agreed that those intense, dangerous 36 days had helped shape the direction and meaning of the life experiences that would follow. For Dave Roberts, it would launch a career as an adventure writer. For me, it would lead to a lifetime of taking risks, many of them in the U.S. Foreign Service. For all of us, it had been a rite of passage.

Jon Krakauer, in Eiger Dreams, describes the “Harvard Route” up the Wickersham Wall as a climb “so bold or foolish…that it still hasn’t been repeated.” At least one person has died trying. Recalling the dangers, the technical challenges, the intense coordination and massive physical effort required over weeks—and, yes, in retrospect, a whole lot of luck—I think we all marveled that we did it, and are alive to tell the tale.